Written by Visit Stampede / Photo Credits: Calgary Stampede

From the earliest days of Calgary’s fairs in the late 1800s, Indigenous peoples were not just attendees—they were at the very heart of the celebrations, enchanting crowds with their dances, regalia, and rich traditions. However, as the 20th century began, the federal government’s assimilationist policies sought to erase this legacy. Under the Indian Act, Indigenous people were forbidden from leaving their reserves without permission, and their languages, ceremonies, and cultural expressions were actively suppressed. The Department of Indian Affairs viewed public displays of Indigenous identity as a threat to their mission of “civilising” First Nations, and worked tirelessly to keep Indigenous people out of public life.

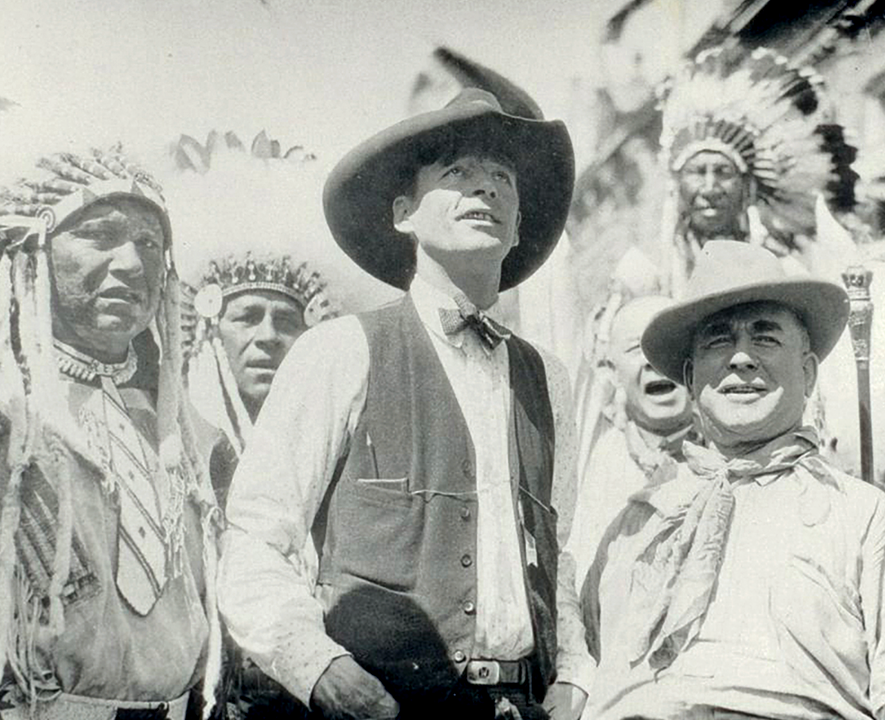

Into this struggle stepped Guy Weadick, an American rodeo promoter with a bold vision for a grand celebration of the West—one that would honour not only cowboys but also the essential role of Indigenous peoples in shaping the region’s history. Weadick’s dream clashed head-on with the government’s agenda. When he requested permission for robust Indigenous participation at the 1912 Calgary Stampede, federal officials balked, fearing a revival of the very traditions they were trying to eliminate. The stakes were enormous: the government’s policies threatened not only participation but the survival of Indigenous culture in public spaces.

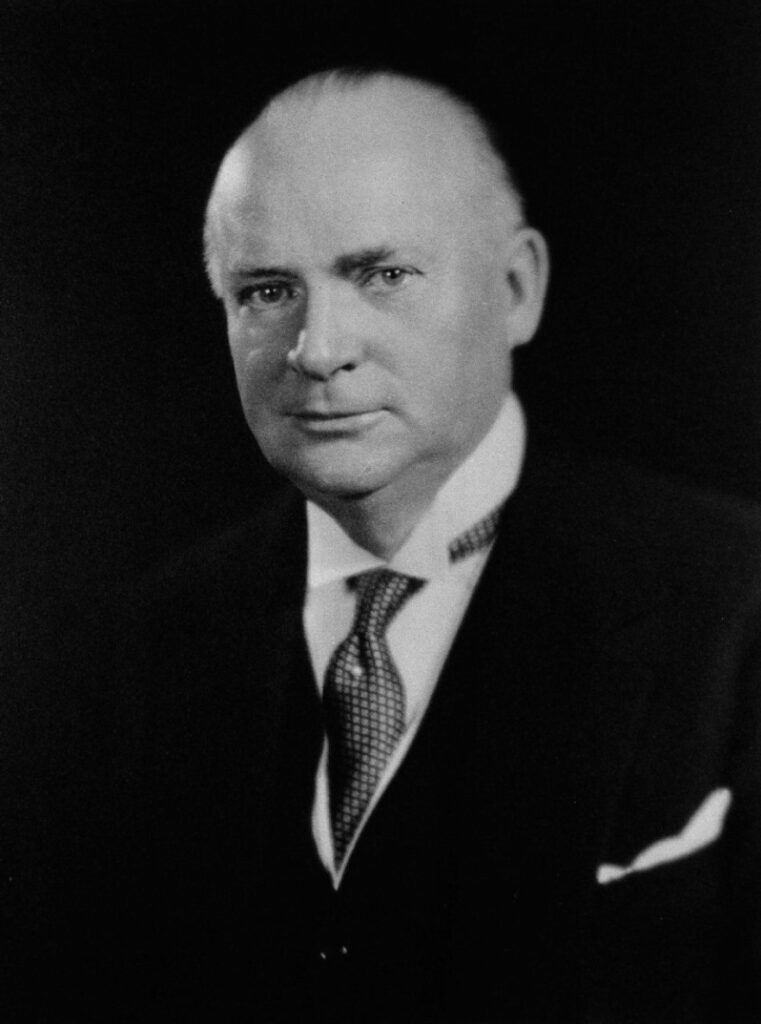

But Weadick refused to give in. He turned to powerful allies—including Senator James Alexander Lougheed and future Prime Minister R.B. Bennett—and together they pressured the government for an exemption. Their persistence paid off: in 1912, nearly 1,800 First Nations people from Treaty 7 led the Stampede parade, camped along the Elbow River, and competed in rodeo events, proudly wearing their traditional regalia. Among them was Tom Three Persons, a Kainai cowboy whose legendary ride on the unrideable bronco Cyclone stunned the crowd and made him the first Canadian and Indigenous champion of the Stampede.

Despite this triumph, the government’s resistance did not end. In 1914, new laws were introduced to further restrict Indigenous participation in public events, aiming to silence their voices once more. Yet the people of Calgary—ranchers, business owners, and everyday citizens—stood with their Indigenous neighbours, knowing that the Stampede was incomplete without them. Their collective outcry was a powerful act of resistance, proving that the spirit of inclusion was stronger than the forces of exclusion.

The struggle continued for decades, with periodic attempts by Indian Affairs to limit Indigenous presence at the Stampede. Through persistence and partnership, the Indian Village—now known as Elbow River Camp—became a permanent fixture, a living testament to the resilience and vibrancy of Treaty 7 Nations. Today, Elbow River Camp stands as a beacon of cultural pride, where traditions are celebrated, stories are shared, and history is honoured.

The legacy of this fight is profound. Guy Weadick’s vision, the courage of Indigenous peoples, and the solidarity of the Calgary community ensured that the Stampede became more than a rodeo—it became a celebration of the true spirit of the West, rooted in the land and the people who have always called it home.

Call to Action

The story of Indigenous inclusion at the Calgary Stampede is a chapter of defiance, hope, and enduring strength. To honour this legacy, visit Elbow River Camp, listen to the stories of Treaty 7 Nations, and celebrate the traditions that continue to shape the Greatest Outdoor Show on Earth.